Long-standing readers will know my penchant for all things Japanese. I also love photography and there are two exhibitions in London that straddle the two domains – Hiroshi Sugimoto and Daido Moriyama.

The latter is on my early new year to-do list but we visited the Sugimoto’s show at the Hayward Gallery on London’s South Bank in the quiet days before starting back to work again.

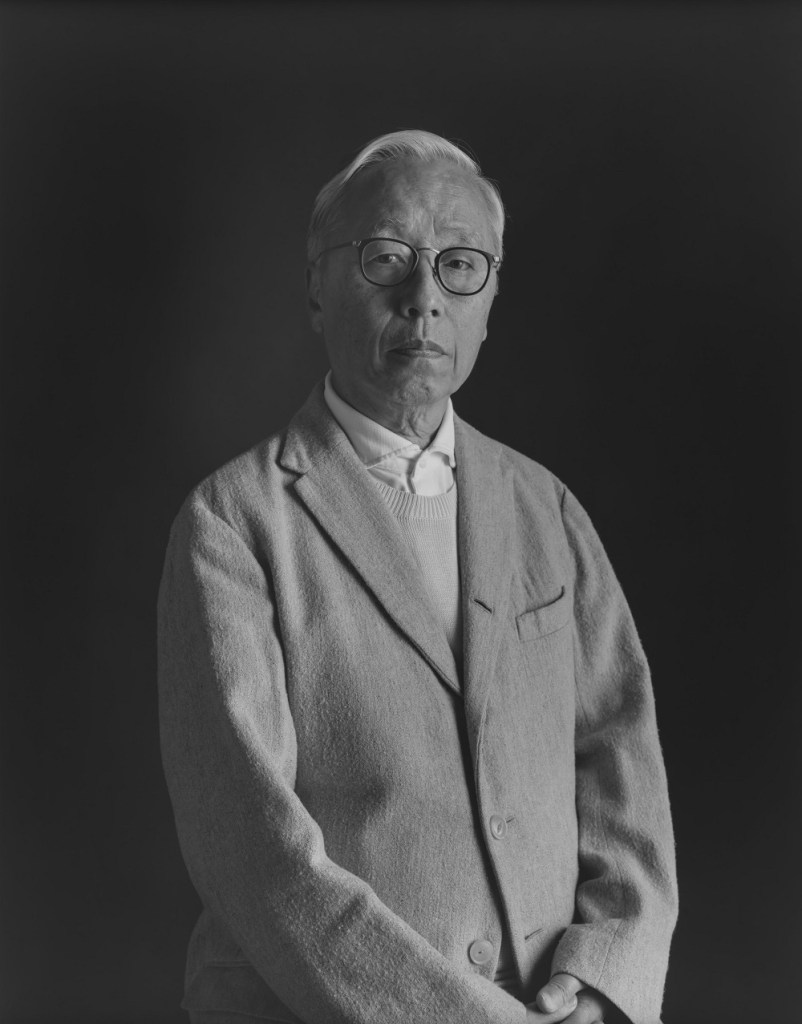

Sugomito was born in 1948 and has spent the majority of his life in Tokyo. He has his own architectural studio, and buildings find a way into his work. He specialises in large format images, similar to Andreas Gursky. For example, he has taken a series of photographs of theatres and drive-through cinemas, leaving the camera on an extremely long shutter, lit only by the movie. The single point of light illuminates the auditorium, creating a focused sense of magic. It reminded us of James Turrell’s work that we’d seen at the Chichu Museum on the Japanese island of Naoshima.

The large format means the building’s lines remain square and true, without the distortion one sees on wide-angle iPhone shots. Sugimoto’s images take in golden age cinemas, baroque opera houses and disused real estate. The drive-in images resonated with me. It captured a sense of the otherworldly excitement of this American concept – watching a movie outdoors, in your car.

The exhibition is called Time Machine, which speaks to the camera’s ability to capture the passage of seconds, minutes or even years. This is evident in a series of rooms, some more satisfying than others. His photographs of seascapes with the sky and water splitting the image in two were powerful and beautiful, especially given the December 2023 earthquakes and potential tsunamis in Japan. I was my other half, whose family were Aberdonian trawler owners back in the last century. She recognised the power of the sea to give and take back. I’ve just finished reading Chris Broad’s account of his years teaching in Japan and his emotional chapters about the survivors of the 2011 tsunami were fresh in my mind.

What worked less well emotionally for me was when Sugimoto tried to capture the artificial. There were some beautiful shots of dioramas of animals that were captivating until you realised that the animals were stuffed exhibits from the Natural History Museum in New York. Another room had him capturing Madame Tussaud exhibits against a black backdrop, creating high-definition photos of replicas of Queen Victoria and Napoleon, amongst others. I know he was trying to highlight the artificial nature of fame, but it didn’t quite click. The models were still made of wax, and their dull patina was evident. What drew me into the seascape and theatre images was absent from these photographs despite the unquestionable technique involved.

The other outstanding room was a blast of colour from a series of enlarged polaroids. Sugimoto used a complex system of lenses and mirrors to capture interstitial colours between primary and secondary. These were like real-life Rothkos, vibrant, inviting you to dive in. Against the black, whites and greys of the remainder of the exhibition, it was a bolt of joy.

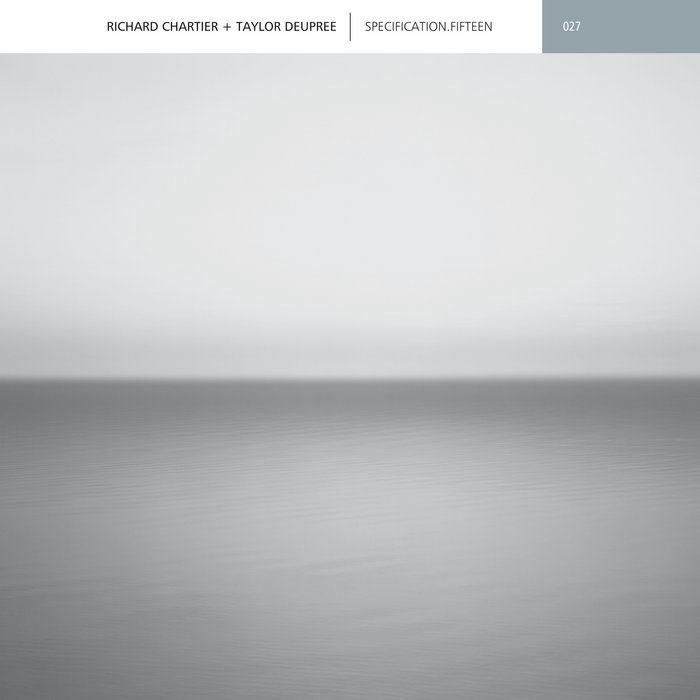

The seascapes may be familiar to music fans. Bono approached Sugimoto to use one of his photos for U2’s 2009 record, No Line on the Horizon. Sugimoto let them use it for free, on the proviso that firstly, no text was used on the sleeve and also that he could use the title track in future artwork. Apparently, he heard a demo of the title song, liked what he heard and was happy for an artist-to-artist trade.

There was some controversy around this as Ryuichi Sakamoto collaborator Taylor Dupree had recently used the same image for his recent album Specification Fifteen. Dupree accused U2 of plagiarism. Dupree’s album was commissioned by a museum in Washington and contact was made with Sugimoto. The work was a collaboration with Richard Chartier, inspired by the Seascape images. The question appears to be whether Bono and the boys had seen the Dupree album cover, a niche sound installation work. I’m judging no one, it is quite possible that U2 made the connection without seeing the earlier Dupree/Chartier record, given its limited production run.

At his best Sugimoto’s work in the gallery was joyful, emotional and moving. On a damp early January afternoon, that’s good enough for me.