Artists are taking control of their legacy in differing ways. Bob Dylan appears to have embraced the vault trailing Bootleg series as a way of ensuring he has some control over the way his music is presented before he passes. He’s not alone in this. Every week we get another Super Deluxe Edition, a classic album or era with endless demos and live versions.

Technology is increasingly making a difference. The Beatles Now And Then single wouldn’t have been possible until recently due to its use of Peter Jackson’s technology. ABBA’s Voyage equally relies on both on the tech but also the artist’s active consent to create a unique legacy based on their own flesh and blood, something corporeal.

This is what Ryuichi Sakamoto’s Kagami (which translates from Japanese as mirror) is about. How do I present myself to my audience when I am not around, knowing that new opportunities exist beyond endless reissues of my music?

This is made all the more poignant by Sakamoto’s death in 2023. It wasn’t his first cancer illness and for a long time, it was clear that he was aware that his life was going to be limited. The documentary movie Coda was evidence of this. The last few years of his life balanced the creation of new music, mostly via soundtracks, and the cataloguing of work already created, such as the V.I.R.U.S. albums with Alva Noto, which were remastered and reissued over the last year.

Somewhat out of the blue, we also got an album of new music from Sakamoto last year, 12. This is akin to a diary with ambient entries by date with little post-production. It was a gorgeous slice of what Sakamoto did best, creating warmth, detail but also with memorable melodies.

The melodic element is key to Kamagi. This is a fifty-minute presentation of his music interpreted for solo piano. These are discrete songs rather than one long flowing piece.

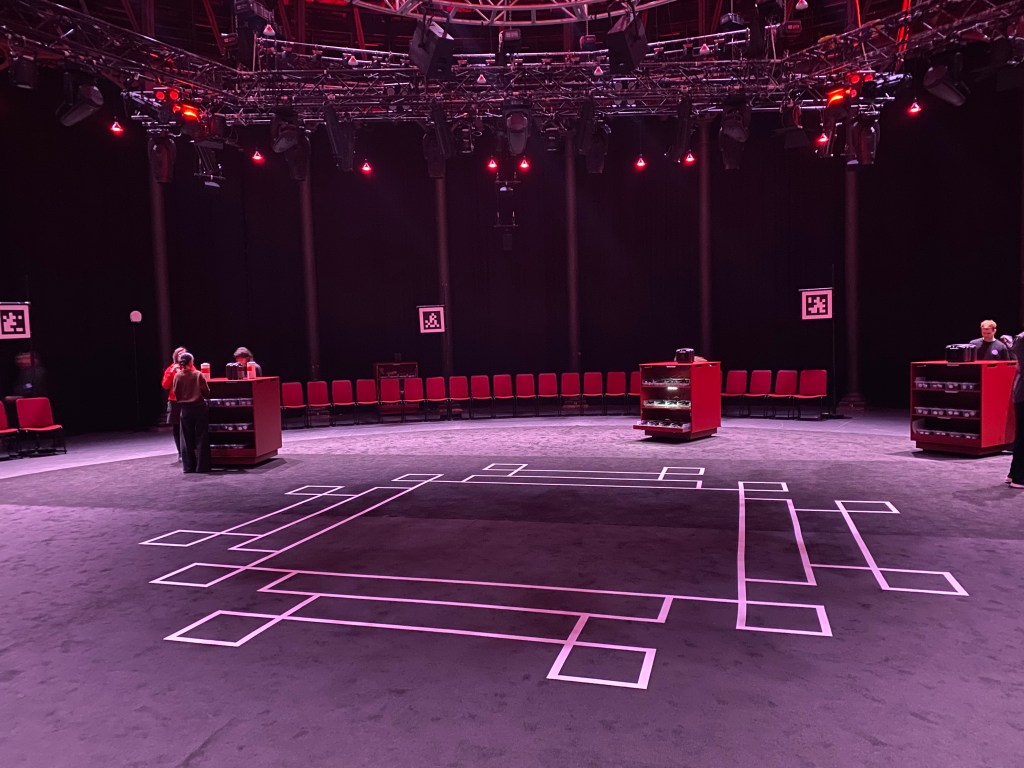

The visual aspect is the revolutionary part. It’s a Saturday night, and about forty of us are led through an eerily quiet London Roundhouse into the central circular performance space. There are about a hundred chairs around the perimeter. We’re handed some headsets, kind of uber spectacles with vision correction for those with a prescription.

On the floor in the centre of the room are some lines, and when we look at the area through our glasses, we see a rotating red three-dimensional cube. We are told that whilst we are seated, we are also encouraged to walk around the performance space. There are only two rules: don’t step over the white lines, and be careful about bumping into people in the dark.

The house lights go down, and an image flickers into life. Before us is Ryuichi Sakamoto, in a dark two-piece suit, sat at a grand piano. He starts playing Before Long, the opening track from 1987’s Neo Geo, and the sound design has the music projecting from the centrally located piano.

As the song plays, soft white clouds cluster on the floor, billowing gently. Most of us stay seated for this first song, taking in the surroundings, adjusting to the technology and probably displaying a little British reticence of being the first people to get more immersive.

It is an unadorned version of Before Long, emphasising that trademark sense of beauty. He starts playing Aenoko No Torso, from Smoochy. Stately and gentle, the album’s Brazilian influence seeping through, It is a solo performance, removing the original’s string arrangement.

I decide to stand up and circle the piano. The sense of physicality is well achieved. As you move through the space, the piano stays static, and your glasses smoothly take you around the instrument, mimicking the scale of the instrument.

Sakamoto began working with technology company Tin Drum in 2019 on the production and completed it just before he died. It is clearly on a different scale, both in terms of performance space and financial budget to Abba’s Voyage performance. He was bought into the exercise, though. This isn’t some ghoulish hologram conjured up to retrospectively monetize his legacy.

Tin Drum’s Todd Eckert described it as follows:

Kagami is not meant to be a historical overview of his career at all. It’s supposed to be an energetic snapshot.

Todd Eckert via the NME website

The more I listen to Sakamoto and explore his enormous back catalogue via streaming, the more important he becomes to me. His stylistic leaps and commitment to his art put him almost on a par with David Bowie, with whom he spent a few months on the Polynesian island of Raratonga filming Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence. They’d met previously and enjoyed each other’s company. Sakamoto was surprised by how down-to-earth Bowie was.

As Sakamoto performs the theme from the movie, I walk behind him and gasp. I’m standing inches from him, looking over his shoulder watching his fingers move across the keyboard. It is a privilege that I’ve never been offered to a musician, to be so spatially intimate and able to vary one’s viewpoint almost at will.

The piece means a great deal to me and I well up. It is a beautiful piece of music and represents the intersection of three of my favourite musicians – Bowie, Sakamoto and David Sylvian who performed the vocal version of the song, Forbidden Colours. It was around the same time that I got properly into all artists as a 15 year old. Bowie was at his commercial peak, Sakamoto was moving on from Yellow Magic Orchestra and Sylvian had just left his band Japan.

The production company have been sharing audience reaction videos on social media and this emotional response is a common theme. It is perhaps made poignant by Sakamoto’s death but this is music that means a huge amount to people. It has a spiritual connection.

As the production moves on, the backdrop around Sakamoto changes and the lighting alters. Sometimes the focus is around him, other times it is around the performance space running floor to ceiling. The intimate detail isn’t quite sharp (which may be down to my long-sightedness), but it doesn’t significantly lessen the performance. I know he isn’t in the room and now never will be, but as an artist-generated experience, it is very special.

This time of experience is probably going to become more commonplace. I think the key for this (and I’ve heard people tell me the same thing about Abba Voyage) is that it is done with the artist’s consent and involvement. It is on their terms and is no more or less valid than the black disc we pop on our record player or the stream of ones and zeroes we hear through our phones.

The final song is BB, a previously unheard piece he composed on the day his friend, Bernardo Bertolucci died. He performed BB at the film director’s funeral. They’d worked together on 1987’s The Last Emperor and Sheltering Sky. As the song progressed, it may have been my perception, but Sakamoto appeared to fade away, his body becoming translucent.

I have to confess that since seeing Kagami I’ve mostly been listening to either Sakamoto or his collaborator Alva Noto‘s music. It’s been a beautiful week reflecting on something I found emotionally uplifting. I’m discovering more joy and more detail each time I listen.

The final word has to go to the man himself.

There is, in reality, a virtual me. This virtual me will not age and will continue to play the piano for years, decades, centuries.

LOVE this so much. I replay again and again when I need to center my being. thank you for what you have given to us.

LikeLiked by 1 person